As we observe the passage of time, it becomes evident that significant crises in human history are often succeeded by periods of renewal. Amidst the tumultuous clash of emotions and enlightened individuals, there have arisen those who have restored equilibrium, guiding many to rediscover the strength to live and the purpose of their existence. The interwar era, heavily influenced by Western ideals in society and culture, gave rise to a response in the form of poets and scientists who fervently explored the realms of sanctity.

The main source of documentation was primarily Sandu Tudor’s library, which we previously discussed in an earlier article regarding his personality. The library was enriched with new volumes that would serve as a manual for behavior and living, following the gentle utterance of the Most Holy Name of Jesus. Sandu Tudor’s cultural interests and pursuits are largely reflected in the books he acquired, most of which were in French and obtained from Paris, ensuring that he stayed well-informed.

The complete fate of Sandu Tudor’s books remains uncertain to this day, and we believe that his library was far more extensive than the approximately 530 volumes currently preserved in the Synodal Library.

It’s worth noting that some of Sandu Tudor’s books remained in Rarău but were later confiscated by the Securitate, along with certain manuscripts. However, the exact fate of these books is not fully known. On the other hand, Father Petroniu Tănase (from Athos), at that time the Starets of Slatina Monastery, received the manuscripts back and later handed them over to the Library of the Holy Synod, safely concealed in a trunk, to protect them from prying eyes. Similarly, Metropolitan Bartolomeu Anania, who had a close connection to Sandu Tudor and had resided at the Antim Monastery, retained some manuscript pages from Sandu Tudor’s collection. Additionally, a portion of Sandu Tudor’s books were left under the care of Brother Andrei Scrima at the Antim Monastery. In April 1959, Archimandrite Paul Bogdan, who was relocating to Plumbuita Monastery, informed the Patriarchate that Father Daniil Sandu Tudor had left this collection in Brother Andrei’s care. To ensure their preservation, the Patriarchate incorporated these books into the newly established Library of the Holy Synod, then known as the “Patriarchate Library.” Following his arrest in 1958, Sandu Tudor had entrusted some of his manuscripts to the priest-academician Nicolae M. Popescu. These manuscripts were then passed on to Professor Alexandru Dimcea, a trusted associate of Archimandrite Grigorie Băbuş, who served as the director of the Library of the Holy Synod for over four decades.

Sandu Tudor’s manuscripts mainly consist of reading notes, personal reflections, as well as the beautiful icons and hymns of the “Rugul Aprins” (“Burning Bush”) Acathist hymn, along with other remarkable writings. These manuscripts were also studied by Metropolitan Antonie Plămădeală, and their publication was diligently overseen by Professor Alexandru Dimcea. However, a systematic theological study and analysis of these writings is deemed necessary.

A unique book collection

In Sandu Tudor’s book collection, religious-themed books dominate, with numerous titles also focusing on philosophy. Some notable titles include P. Pourrat’s “La spiritualité chrétienne” (1926), A. Puech’s “La littérature grecque” (1930), F. Cayré’s “Précis de patrologie” (1931-1933), Grégoire le Grand’s “Dialogues” (Paris, 1875), S. Augustin’s “La cité de Dieu,” S. Cyprien’s “Sermon sur l’oraison de Notre Seigneur” (Paris, 1663), alongside authors like Vl. Soloviov, N. Berdiaeff, J. Maritain, Nietzsche, Freud, Jung, and Schopenhauer. Literature is also represented, with works by A. Daudet, F. Dostoevsky, Fr. Villon, G. Flaubert, G. Papini, R. Roland, and the renowned Pierre Larousse’s “Le Grand Dictionnaire” (Paris, 1875) in 16 volumes in-folio. The collection also includes well-known works on literary theory, literary criticism, studies on the history of Christianity and monastic life, Byzantine art, religious meditations, history of mentalities, as well as a series of notable theological periodicals, such as “Irénikon,” “Orientalia Christiana,” and “Nouvelle Revue Théologique.” These elegantly bound volumes constitute a distinct section within the Library of the Holy Synod. However, the most significant volumes are the 12 Romanian manuscripts written in Cyrillic script, compiled in the late 18th and early 19th centuries by disciples of the holy abbot Paisie of Neamţ. These manuscripts contain translations from the great mystics of Orthodoxy: Patriarchs Calist and Ignatie, Gregory of Sinai, Isaac the Syrian, Saints Varsanufie and Ioan, and Basil of Poiana Mărului, included in the famous collections “Crinii Ţarinii” (Lily of the Valley) and “Floarea Darurilor,” (the Flower of Gifts) which were widely circulated throughout the country. The manuscripts were copied either in Moldavia, in places like Râşca, Secu, Agapia, or in Wallachia, at the Ţigăneşti Skete or Bistriţa Vâlcea., nor are those copied at Prodromu by the humble hieromonk Paisie Lambru. Some of these miscellanies bear the forced mention “found during the search of Sandu Tudor,” along with the signature of the officer who conducted the search.

“Prayer and Hope: A Path to Holiness”

The burning bush, seen by Moses on Mount Sinai (Exodus 3:2-5), symbolized the divine revelations he received. Similarly, continuous prayer, offered with attentiveness and humility and through God’s help and mercy, invites Jesus into our hearts, filling them with joy and heavenly grace.

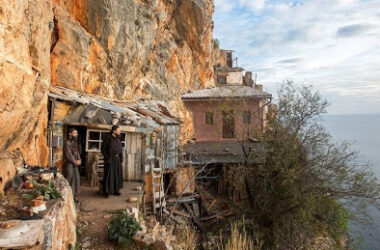

Did the members of this group know that they were being prepared and taught by divine mercy to withstand the terrifying and deadly wave of communism? This oppressive regime falsely accused them of plotting against social order. However, those who resonated with the spirit of the “Rugul Aprins” prayer group remained steadfast through prayer and hope, even in the face of unimaginable demonic torment in communist prisons. In 1948, their gatherings declined due to the new regime’s disapproval of the mystical activities associated with the “Rugul Aprins” movement, which eventually ended in 1950. Anticipating persecution, Patriarch Justinian hid some monks from Antim Monastery in remote monastic communities across the country. Agaton Sandu Tudor, too, was transferred to Crasna-Gorj Skete in 1950, where he was ordained as a hieromonk by Metropolitan Firmilian of Oltenia. Although he was later arrested on false charges related to wartime activities, he was released in 1952 and received the monastic tonsure at Sihăstria Monastery, assuming the name Daniil. He went on to serve as the abbot of Rarău Skete, dedicating himself to unceasing prayer. During the years 1954-1958, he made occasional extended visits to his acquaintances in Bucharest, where he would meet with them in small groups. However, on the fateful night of June 13-14, 1958, he, along with Alexandru Mironescu and his son Şerban, was arrested from Alexandru’s residence. This arrest was part of a larger group apprehended for their involvement in the “Rugul Aprins” movement, collectively known as the Alexandru Teodorescu group. Among its members were revered figures such as Fathers Arsenie Papacioc, Sofian Boghiu, Benedict Ghiuş, Roman Braga, Felix Dubneac, and Dumitru Stăniloae, totaling 16 individuals. Hieromonk Daniil Sandu Tudor, like many others, was then sent to Aiud prison, embarking on a journey from which he would not return. It is believed that he died in 1962 as a result of the severe beatings and torture he endured. But why and what kind of threat to the people or social order did he pose? In reality, his true offense was instilling the fervor and communal spirit of prayer in countless influential individuals, openly challenging the atheistic regime that would oppress the Romanian Orthodox people for over four decades. Perhaps the shedding of Father Daniil’s blood, along with that of many other martyrs from the communist prisons, will bring divine forgiveness upon the nation that, for the most part, endured the demonic yoke of the red beast without resistance. Our only response is to humbly seek forgiveness and continue our loving efforts to share Christ with others.

The “Rugul Aprins” movement has yielded results, fulfilling its mission to guide towards holiness and sanctification. Its impact is witnessed by the devoted disciples, passionately filled with love for the crucified and risen Christ.

(I express my gratitude to Professor Gheorghe Vasilescu, the Head of the Holy Synod Archives, for his kindness in granting me access to the necessary documents.)

Archimandrite Policarp Chiţulescu

Source: http://ziarullumina.ro

The English translation of “Crinii Ţarinii” is “Lily of the Valley”

“Floarea Darurilor,” is “The Flower of Gifts.

“Rugul aprins” is “ The Burning Bush”